Normally my Fool Britannia pieces get their laughs by poking fun (good naturedly I hope) at the eccentrics who engage in the wackier side of British culture. But this time out I’m going to be more personally invested in this latest instalment, because the subject I’ll be exploring was a massive influence on my early years and while it is something that is a cornerstone of British sporting culture, my own love of it went past fandom and into the realms of obsession.

You see this weekend sees the greatest race of any kind take place at Aintree race course, The Grand National. The National is the one horse race of the year that the general public truly gets excited for. Workplaces across the land will hold sweep stakes and on Saturday morning bookies everywhere will be crammed full of novice gamblers asking such questions as:

“How do I put a bet on “Rampant Sex Drive?”

“What does 3-1 mean?”

And “why does that old man in the flat cap sat by the slot machines smell like piss?”

It’s been called the people’s race and with good reason. Normally horse racing is the domain of the upper classes, with posh idiots poncing about in expensive and gaudy outfits, men in top hats and women dressed like bleeding Carmen Miranda and generally looking like complete pillocks at events such as Ascot and The Derby. However beneath all the nonsense from the chinless wonders they’re essentially just run of the mill races.

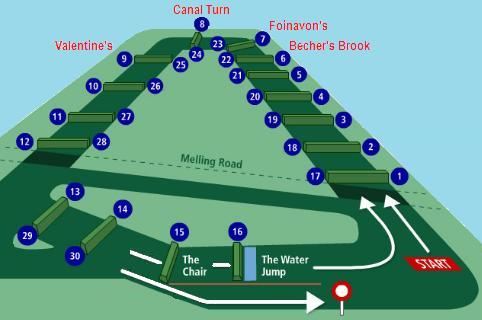

The Grand National on the other hand is an absolute spectacle, four miles of insane demolition derby carnage as a field of no less than 40 horses stampede over 30 fences, some of them so fearsome they’ve become icons such as Beechers Brooke, The Chair and the Canal Turn (so called as it sits right before a 90 degree turn in the direction of the course).

It’s the most unpredictable sporting event you’ll ever see. Most years only half the runners will actually make it over the finish line, other times that many will already have fallen by the end of the first lap. Luck as much as judgement plays a hand in successfully picking a winner as even the most heavily fancied favourite can find itself stuck in the throng at the first fence and having it’s chances royally buggered by having a horse fall directly in it’s path.

It’s a breathtaking eight minutes and so intense is the action that it takes three commentators passing announcing duties from one to the other relay style to get through the race.

As long as I could remember I’ve been captivated by this race. When I was at school I amazed and amused my teachers during drawing time as while other kids were sketching trains and castles and the like I was drawing scenes from the Grand National. The drawings started as stick men jockeys on stick like horses and steadily progressed through the years to cartoon like comic strips featuring a page for every single fence jumped, sometimes they’d be an exact retelling of the actual race and sometimes my own fantasy creations. The races that I’d made up I’d even do my own commentary, talking aloud and mimicking the style of the likes of Peter O’Sulleven and even recreating the changeover in commentators, for some reason sometimes adopting an Irish accent.

What can I say? I was different.

Grand National day was as big a deal to me as Christmas Day. I’m serious here I was a weird kid. I would wake up the moment the newspaper fell through the letterbox and I’d immediately grab it and turn to the sport pages that detailed what the colours and patterns of the jockeys shirts and caps would be and with my coloured felt tip pens I’d painstaking create a key to what all the jockeys would be wearing. By the time the race came I’d have them all memorised.

And if this sounds rather bizarre for a six year old to do, consider this: One of my earliest childhood memories had to do with the Grand National. Seriously I was four, barely four as my fourth birthday had been less than on a month before. It was the 1977 Grand National and my favourite racehorse “Andy Pandy” was miles ahead of the rest of the field. Quite why a horse named after a kids TV show that had aired twenty years before I was born was my favourite I have no idea. In fact how a four year old came to have a favourite racehorse in the first place is pretty freaking bizzarre when you come to think of it.

In any case Andy Pandy was out in front and having the run of it’s life (check out the footage on youtube, it was streaks ahead) until it came to the imposing looking Beechers Brooke. Andy Pandy jumped the fench, landed awkwardly and stumbled forward, unseating it’s rider who went arse over tit.

My heart broke in that second. The image is forever etched on my mind of Andy Pandy falling at Beecher’s Brooke as is me howling in distress as my eyes erupted with tears that would not stop flowing for the rest of the race. I bawled my eyes out and was utterly inconsolable and totally oblivious that one of the greatest moments in sporting history was unfolding before my now red raw eyes.

Because 1977 was the year that Red Rum made Grand National history by winning the race for the third time. To put this in perspective only four horses in the races 180 year history won two Grand Nationals before Red Rum and only one of those won in the 20th Century (Reynoldstown in 1935 and 1936). Red Rum became a national treasure and enjoyed a well deserved celebrity retirement, opening supermarkets and literally being a stud, servicing a whole line of eager fillies wanting some of that Red Rum goodness.

Red Rum’s three victories became one of the most famous fairytale stories in British sporting history. However the race has provided many other great stories over the years.

Bob Champion riding Aldaniti in the 1981 National was a triumph in it’s own right as just a few years earlier he’d endured a brutal battle with cancer. Being alive to compete may have seemed victory enough, yet the God’s of Sport declared that they wanted more and so in one of the most emotional and feel good moments in sporting history Champion steered Aldaniti to victory.

In 1904 the race was won by a Moifaa a horse that had been feared lost in a shipwreck on it’s way from New Zealand to Liverpool but was found alive and exhausted on an inhabited island that legend has it the horse had to swim fifty miles to get to. I say “legend” because the story is sadly complete bollocks. Moifaa didn’t even get shipwrecked having a routine ship ride to England. However one of Moifaa’s rivals in the 1904 race Kiora did indeed get shipwrecked around the same time and had to swim to the safety of a reef where it was discovered the next day. Newspaper hacks eager to embrace the story of a Robinson Crusoe horse winning the National got the two horses mixed up, so in my role as Dazza Downer I’m afraid I have to debunk this particular one.

Probably my favourite story coming out of the Grand National was in 1967 when 100-1 Foinavon pulled off the underdog story of the century by finishing first across the line. Foinavon was actually well behind in the race until the race reached the small and rather innocuous 23rd fence. A loose horse ran along the fence and into the path of the leading horses. What followed was absolute carnage as the leading horses halted and those behind crashed into them as wave upon wave of horses piled into a scene that started to resemble a keystone cops movie. Horses were running in all directions, unseated jockeys were desperately chasing after their own rides. Amidst the chaos only one horse, Foinavon, was able to steer clear of the pandemonium and rather limply hop over the 23rd fence successfully.

Most of the causalities at the 23rd fence manage to regroup and carry on the race (rather unusual as generally when a jockey is unseated that’s race over) but Foinavon was too far in front to be caught and jockey John Buckingham rode him home to victory probably wondering what the bloody hell he’d done right in his life.

The most infamous Grand National was that of 1993, the race that was to be starter Keith Brown’s last before retirement although by the day was over he’d probably wished he’d retired a year earlier or at least phoned in sick that day.

Starting a race by lining up 40 horses full of adrenaline armed with only a flag and a line of tape is tricky to say the least. An invasion by animal rights protesters before the start only added to the tension and at the first attempt to start the race a jockey got tangled in the tape (which was not tight enough) and a false start was declared with the field having to be brought back before they reached the first fence. The horses were lined up again and as the rope was raised a jockey got tangled again and once again a false start was declared only this time the flagman who should have signalled to the jockeys to turn back before the first fence did not do so and so thirty of the thirty nine horses carried on oblivious.

While frantic trainers and owners tried to get the attention of their jockeys, bemused announcers were forced to commentate on the progress of a race that frankly didn’t matter. The crowd booed as the riders carried on racing despite officials trying to flag them down (many riders claimed they thought they were protesters trying to disrupt the race) by the end most had realised something was amiss and had pulled up but seven horses rode to the finish with Peter O’sulliven declaring Esha Ness the winner of the “race that surely never was.”

With so many horses spent and the fences in a state of ruin any idea of rerunning the race was a non starter (pardon the pun) so the organisers decided to give up the Grand National of 1993 as a bad job. The only consultation out of the whole fiasco was that for once every person who had put money on the race was able to and collect from the bookies, even if it was just the money they’d bet.

Things have changed obviously since when I was a kid. I no longer draw incessantly cartoons of the race, nor do I do my trademark colour key to the jockey’s uniforms (colour newspapers and the internet has made that redundant) and even I’m not weird enough to sit in my room and pretend I’m commentating on a fictional race.

The race itself has changed a lot. Safety concerns for both horses and riders has meant many of the fences have been made smaller and less dangerous, especially at the notorious Beecher’s Brooke (where my beloved Andy Pandy had it’s dreams of victory destroyed) where the ground has been made more even and less hazardous. Today the field is never made up of more than forty runners, far cry from when over sixty horses would sometimes compete.

Still even with these modifications the race is still very dangerous and sadly some horses have died or had to be destroyed during the race. While the event still enjoys a massive popularity for casual sports fans it has come under fire in recent years, especially following the deaths of two horses in 2011 and another two in 2012.

But despite the sour feeling that comes with the possibility of harm coming to the magnificent horses in the Grand National, I still absolutely love that race. I’ll spend all Saturday morning picking my bets, based on the scientific method of choosing a horse with a sci fi sounding name and a jockey with cool looking colours. And I’ll watch the build all day and get goosebumps as the race gets nearer and the long parade of the horses begins on it’s pilgrimage to the startline.

And at some moment, the day will remind me of my childhood and how this one race inspired so much passion and creativity in someone so young. And how it meant so much to me that I would refer to with such innocent joy as “My Day.”

And when Beecher’s Brooke lumes into view I’ll think of a four year little boy watching his favourite horse in the lead and about to cry his eyes out.

Dazza

This was lovely.