In boxing, multi-divisional champions are nothing new. Hector Camacho held seven titles across the 130-to-168 pound weight classes, Tommy Hearns held championships in five weight classes from 147 pounds to 175 pounds and Roy Jones, Jr. held five championships spanning 160 pounds to 200 pounds plus. More recently, Floyd Mayweather, Jr., held championship belts at the super featherweight, lightweight, light welterweight, welterweight and light middleweight level, while Manny Pacquiao has been a champion in eight different weight classes, at one point possessing super featherweight, junior lightweight, lightweight, junior welterweight and welterweight belts simultaneously.

In the world of mixed martial arts, however, dual weight-class champions are virtually unheard of. In the UFC, only two men – Randy Couture and BJ Penn – have held belts in more than one weight class, and Dan Henderson remains the only fighter in a major MMA promotion to hold two championships in two different divisions simultaneously.

Of course, there is a pretty simple explanation for why weight class jumping is the norm in boxing and relatively rare in MMA. In boxing, the jump from one division to the next is far more incremental, with only five pounds separating super featherweights from lightweights (and just 10 pounds separating a super featherweight from a super lightweight.) Meanwhile, the leap from MMA welterweight to MMA middleweight comprises a differential of 15 pounds, which in boxing, would cover at least four different weight classes (and in the smaller divisions, sometimes even more than that.)

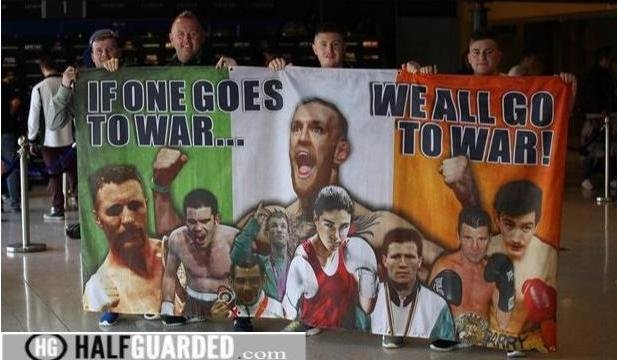

Which makes Conor McGregor’s bout against Nate Diaz at UFC 196 – in which the phenomenally popular Featherweight Champion will move up 25 pounds – all the more remarkable.

Sure, we’ve seen 20-pound jumps before – Vitor Belfort, for instance, leapt from Middleweight to Light Heavyweight for an ill-fated matchup against Jon Jones in 2012, and Anderson Silva has left the cozy confines of the 185-pound division for several excursions into the 205-pound zone (albeit, against less than sterling competition.) But by and large, such moves are uncommon, and McGregor’s double weight class jump is virtually unprecedented in modern MMA.

Whatever doubts existed regarding McGregor’s abilities were repudiated last December, when he annihilated long-time 145-pound champ Jose Aldo in 13 seconds. Originally set to go toe-to-toe with Lightweight Champion Rafael dos Anjos, “The Notorious” instead locks horns this Saturday with veteran slugger Nate Diaz in a last-minute welterweight clash that could have huge implications for the sport.

Technically, the bout is a jump up for Diaz, as well, whose last bout was a 155-pound tilt against Michael Johnson Dec. 19. Nonetheless, it’s a much larger jump up for McGregor, even if his “walking around weight” is believed to be 174 pounds.

If McGregor wins, it would firmly establish him as a legitimate title contender in not just two, but three weight classes. That sets the stage for a deluge of big money fights across the 145 to 170 pound spectrum, including the prospects of both Lightweight and Welterweight Championship bids.

There simply is no Conor McGregor weight class – there is just money-weight

This is significant because, historically, championship fighters have remain locked into their respective divisions. Even Georges St-Pierre, the most dominant UFC champion of all-time, refused to step outside the 170-pound comfort zone, despite laying waste to the entire division and getting to a point where he had to recycle challengers. McGregor, then, may represent MMA’s first division-fluid star, a bankable competitor whose pool of potential bouts is three times that of other fighters.

In an injury-plagued sport – where last-minute cancellations routinely scuttle pay-per-view affairs – having a breakout star capable of filling in at multiple weight classes is a godsend. Moreover, McGregor’s trans-divisional sojourning may convince other fighters to at least mull packing on the pounds for inter-weight class showdowns, which means instead of dropping bouts (and sometimes entire shows) because of an injury, we could end up with makeshift dream fights coming true left and right.

Daniel Cormier pulls a hammy ahead of his tilt against Jon Jones this April? Well, how about letting Jones test his mettle against an established heavyweight – an Arlovski or a dos Santos – instead of keeping him sidelined and squandering the PPV revenue? Henry Cejudo gets hurt sparring, and Demetrious Johnson is without a dancing partner? Tell Mighty Mouse to hit the buffet line, ‘cause he’s got a bantamweight scrap with Urijah Faber as a replacement.

Of course, such scenarios remain at the discretion of the fighters. Not everybody on the roster is as fight-happy as McGregor or Donald Cerrone, and something tells me notorious prima donnas like Fabricio Werdum would rather take the stay-at-home route than risk losing against a late substitution. However, if you can dangle the same carrot in front of them that McGregor reportedly received at UFC 194 (he’s alleged to have gotten a $3 to $5 cut from all PPV sales, meaning he may have taken home anywhere from $3.5 to $6 million in bonus pay on top of the cool half mil he was paid to step inside the Octagon), main eventers may not have the luxury of turning down last second matchups anymore.

Even in a losing effort, McGregor’s foray outside his divisional confines this weekend could set an extremely significant precedent for the sport. No longer bound by rigid weight class limitations, top fighters can now feel free to test the waters above – and below – them. Instead of being deterred by interdivisional contests and taking bouts on short notice, the financial incentive of headlining a PPV card – even at $1 per buy, that’s far more money than most fighters receive in fight night pay – could goad them into inking the dotted line. And as a result, we could get the big-money fantasy contests we thought we’d never see in a million years – Aldo vs. Cerrone, Condit vs. Rockhold, Gustafsson vs. Miocic, etc. – on a regular basis.

Before all of that can happen, however, McGregor has to make his way past Diaz on Saturday, which is anything but a guarantee. Indeed, if Diaz were to go in there and drop McGregor early, not only would that derail the Conor gravy train, it would reinforce the “sanctity,” so to speak, of the unstated affixed weight class diktat.

But if McGregor can go in there and demonstrably prove that a fighter can be a legitimate threat 25 pounds beyond his supposed divisional limit? Not only would it be one of the biggest statements in MMA history, it would be one that could drastically alter the trajectory of the sport forever.

And if McGregor has it his way, it means weight will be nothing more than just another number in the wild, woolly world of mixed martial arts.

Comments 1