The 60’s has become known as the revolutionary decade of peace, love, sex and drugs. Well Woodstock culture was a bit way off, as evident by the major news stories of the year, with America sending troops in Vietnam (gonna work out swimmingly), the IRA starting action against the British, Castro starting to nationalise US interests in Cuba and the Soviets shooting down a US spy plane. But Chubby Checker introduced young un’s to the Twist, so that was nice.

As far as movies go the Hollywood film industry was in flux for many complicated reasons, so make it simple we’ll just say it was all television’s fault. The serious implications of rivaling this new upstart form of entertainment was studios forced to take risks with massive, epic and expensive movies in order to get people off their arses and into theatres. Meanwhile teen audiences were looking more and more appealing, with not only monster and sci fi movies flooding drive ins in the late 50’s but a more rebellious teen angst vibe with films like Rebel without a Cause and the Wild One. Ever so slightly, some films were starting to get a little more raunchy too.

For me, these were the films of 1960 that left an impression.

Spartacus Director: Stanley Kubrick

A gladiator leads an army of slaves against the might of the Roman Empire in an attempt to win their freedom.

If ever there was a film that embodied all that Hollywood was banking it’s survival on, it is Spartacus. Epic in it’s scale of a movie, length, budget and star power, it came about with Kirk Douglas’s disappointment of failing to land the lead role in Ben Hur and his desire to make a similar sands and sandals film and just as massive. It succeeding in wowing audiences with glorious visuals, action, romance and became the number one box office film of the year. It was also subversively political, a true rebellious film from it’s very inception.

Kirk Douglas’s Spartacus is based on a real historical figure (111-71 BC) who led and army of escaped slaves in rebellion against the Roman Empire. We follow Spartacus as his proud defiance as a slave leads to him being sentenced to death by starvation, but is bought by the owner of a gladiator school (a fantastic performance by Peter Ustinov). During his training Spartacus falls for a beautiful slave girl (Jean Simmons) for which they are both mocked and humiliated by the school’s trainers. Following an incident in a contest to the death where an African gladiator refuses to kill him and pays for it with his life, Spartacus rebels and he and the other gladiators take over the school. The slaves set out to escape Italy, freeing and recruiting more slaves along the way and forming a massive army that causes the Roman Senate to give emergency powers to an ambitious and cruel leader in Crassus (Laurence Olivier as a chilling and hateful villain) to crush the uprising.

Spartacus is one of those movies that became a curious choice for traditional Christmas television schedules here in the UK. When I was a kid most of my first time viewings of classic films were over the Christmas period (and sometimes Bank Holiday Mondays), so much so that the imperfect technicolour tone of 50’s and 60’s films often feels synonymous for me with the taste of mince pies and leftover turkey sandwiches. Spartacus is one such movie that I routinely watched with the family during Christmas, eating up a whopping three hours of the festive season.

Quite how I coped with Spartacus as a kid I can’t remember, because it’s a long and sometimes slow paced movie, yet it’s suitably so. We spend over 40 minutes at the Gladiator school, watching as Spartacus’s warrior and military prowess grows as much as his resentment. Douglas barely speaks for much of the movie, yet his restrained despair and his rage is all in his eyes, a proud strength even in the face of abuse and torture. He’s an incredible, stoic figure, a powerful warrior but one that also breaks our heart with the mistreatment he endures.

Like many films it seems I saw as a kid, Spartacus is a real downer. After finding a brief taste freedom and enough time with his lover to have a child (even to a romantic like me the romance scenes with Douglas and Simmons are very sickly sweet),, Spartacus’s revolutions come to a head with a showdown with the Roman legions in massive battle scenes that with their breathtaking scale, realism and brutality still convey more awe today than most CGI created depictions of war. Defeated, he becomes a figure to be broken by his opposite number Crassus who’s plainly afraid and jealous of the legend of Spartacus. He’s tortured by the knowledge that his wife Varinia and child are destined to live as slaves in Crassus’s household and then forced to fight his best friend Antoninus (Tony Curtis) to the death in order to spare him crucifixion and condemn himself to it. The final scene is one of the most gut wrenching, profound and tense finales to a film ever. Spartacus on the cross, seeing his Varinia and his son as they are smuggled out of the city, as she shows that his son is free while begging him to die and be at peace is beautifully tragic, all this as Peter Usitnov begs her to come with him out of the sight of the suspicious Romans.

An early example of a Hollywood Blockbuster, deep in spectacle as a 1960’s crowd pleaser Spartacus may be, but there is also a rebellious symbolism driving a subversive nature both on the screen and in it’s production. At a time when the civil rights movement was on the rise, it’s easy to read a narrative in a film that is about oppressed slaves rising up against a decadent super power in the cause of freedom. The parallels between the Rome portrayed on screen and mid twentieth century America were so on the nose (both societies rise built on slavery, and the rebellion featuring the integration of black and white slaves at a time when segregation still existed in America) that pickets from anti communist groups targeted some screenings. President Kennedy had to cross one such picket line to see the film.

That Spartacus has a strong politic tone is not surprising when looking at the background of the film. The source of the film’s story is the novel by Howard Fast who wrote the book in prison while serving a sentence for refusing to name names in the witch hunts of the House Committee of UnAmerican Activities. The film itself was written by Dalton Trumbo who as one of the Hollywood Ten was on the blacklist and had been writing scripts under a pseudonym. It was Kirk Douglas himself who insisted that Trumbo should be recognised as the screenwriter and was an instrumental step into breaking the Blacklist.

The writer’s experience and mistreatment at the hands of the HUAC surfaces several times in the film. The iconic (and much parodied) scene where the captured and defeated slaves are offered freedom if they will point out Spartacus, resulting in them rising one by one defiantly and claim to be him, is a commentary on the practice of naming names before the HUAC in order to save oneself. Likewise, the political intrigue going on back in Rome with the slave revolt being blown out of proportion to use as a scare tactic for the ambitious Crassus mirrors the schemes of Joseph McCarthy.

Maybe it’s because of this anti authoritarian stance that Spartacus has managed to remain a relevant movie even today, Kirk Douglas’s performance acting as a symbol of defiance and standing up to the establishment.

It also allowed Douglas to even the score against Tony Curtis after losing to him in The Vikings a few years previous.

Saturday Night, Sunday Morning Director: Karel Reisz

A young working class man copes with the mundanity of life as a factory worker by going out on a weekend and having an affair with a married woman.

The film industry in the UK in the 60’s didn’t have the budget to compete with Hollywood’s vast epics, but a more down to earth movement was bringing in the audiences. Dubbed the British New Wave, British cinemas played host to a series of popular films, known as kitchen sink dramas and based on and inspired by the plays and novels of the likes of Alan Sillitoe, Kingsley Amis and John Osborne. These films were designed to show the realities of working class life and invariably used the trope of the angry young man, a figure who would be dissatisfied by being trapped in the work and family cycle of everyday life.

“Nine hundred and fifty four, nine hundred and fifty bloody five. Another four more and that’s the lot for a Friday.” snarls a young Albert Finney in the opening scene, delivering one of the best first lines ever in a British film. It’s a bitter introduction to the character of Arthur Seaton, a disillusioned factory worker in a mundane, repetitive job. Stuck in his job and not keen to fall into the trap of family life ( on his parents he says “They have a TV set and a packet of fags, but they’re both dead from the neck up”), Arthur lives for the weekend, going out drinking and enjoying an affair with the wife of one of his work colleagues

The character of Arthur is one that must have appealed to the youth of the early sixties, rejecting the social norms of starting a family in a council house and instead living a carefree life of drinking, partying and casual sex. He isn’t one to wallow with his lot in life, his motto of “don’t let the buggers get you down,” is indicative how dismissive he is of how he’s expected to live life, and while he has money in his pocket on a weekend he’s content to live in the pursuit of having a good time while he can.

There is a roguish charm to Finney’s portrayal and he ends up with two women in his life. Brenda is the older woman he is having an affair with, their relationship purely based on sex as she too is bored with motherhood and her straight laced husband. Doreen is more of a traditional girlfriend, close to Arthur’s age and who expects marriage down the line and wants to wait before having sex with him. Doreen represents the safe life that Arthur is trying to avoid, while Brenda is the sexually liberated side of his life which leads to drama when he gets her pregnant and when their affair is discovered brings him into conflict with the husband’s violent brothers.

Saturday Night, Sunday Morning proved popular amongst audiences, especially appealing for those who now saw their lives on the big screen (the popular soap Coronation Street started in the same year, which had the same vibe of working class everyday life as most of the British New Wave). Where Saturday Night, Sunday Morning excels is in it’s realism in the presentation of working class life, neither romanticising or pitying life in industrial cities. This is not a tale of poverty or despair, the families portrayed generally live comfortable lives, but it does emphasis a conformity that a young, viral man like Arthur would find repressive and mundane.

The film deals realistically with working class life, highlighting the issues with family life and married strife, as real as sex and the existence of back street abortions, which were still illegal in England at that time. The role of women in early working class 60’s society comes into prominence also. A young girl like Doreen has little prospects beyond the expectation of finding a husband and having babies, not even being afford the social release that Arthur enjoys. Brenda is the probable future for a girl like Doreen, and even though she has a perceived mild mannered husband is slapped hard in public when her affair with Arthur is uncovered at a fairground.

A gritty, down to earth story Saturday Night, Sunday Morning may be, it’s still entertaining and funny with dry humour that’s deliciously quotable. Most of this is thanks to Finney’s electric performance, with a presence that owns the screen with a rebellious swagger that rivals Brando in the Wild One, yet still is rooted in authenticity.

Saturday Night, Sunday Morning is one of the British films ever made. It’s a realistic and grounded slice of everyday life for much of the British public at the time, being biting without falling into the depressing and bleak. It’s also wonderfully ambiguous, with an ending that questions whether a rebel like Arthur can triufely change his spots.

The Magnificent Seven Director: John Sturges

Seven gunfighters are recruited to protect a village of farmers from a vicious bandit.

Nowadays we groan when news from Hollywood breaks that a classic film is going to be remade for 21st century audiences, or a brilliant, well respected foreign movie is to be adapted into an English speaking version because there are those who “Don’t like reading subtitles.” Sometimes however, remaking a film makes sense when it makes a story feel more culturally relatable. Take for example Kurosawa’s 1954 Seven Samurai, it feels totally reasonable to take a film on Japanese folk heroes the Samurai and adapt it for American audiences using their own mythical figure The Gunfighter. Not that it succeeding in appealing to American audiences. Even with a great cast, The Magnificent Seven was a disapointement box office wise, failing to crack the top ten for the year (classic Westerns were starting to fall out of favour and it would take the harder edged Spaghetti invasion to revitalise the genre), and ironically it was over seas markets that saved the film from falling into obscurity.

The Magnificent Seven is another movie that somehow became Christmas viewing for me and would be one I looked out for when working through the Christmas Radio Times to plan my holiday TV watching (having to plan around those annoying family visits) . The film also created that popular pub past time of trying to name the actors in the Seven and would always leave you with one you couldn’t remember (It was always Brad Dexter).

Magnificent Seven follows closely much of the plot of Seven Samurai and features similar characters, although some of the darker twists such as the discovery the villagers had been previously killing Samurai visitors was left out. A small Mexican farming village is constantly been raiding by an army of bandits led by a ruthless Eli Wallach as Calvera. Despite having little wealth a few villagers set out across the boarder into America to try to buy guns.

However when the villagers witness a gunfighter Chris (an iconic role by Yul Brynner), combat a bunch of cowboys trying to prevent a Native American being buried in their graveyard, they ask him for help and he recommends recruiting a team of experienced fighters instead. Brynner recruits an all star cast of Steve McQueen (who Brynner clashed with and refused to do a sequel if McQueen was involved), Charles Bronson, Robert Vaughn, James Coburn, Horst Bucholz and that other bloke no one can remember.

The opening beats of the score of Magnificent Seven can’t help but put a joyful smile on the face of fans of this movie, setting the mood for a fun, old school golden era western with shades of men on a mission. This is heroes and villains, strong men coming to the aid of the weak. There’s more well written humour than found in traditional westerns, with the talented and charismatic cast delivering one liners for all their worth. Especially standing out is the genuinely funny exchange between the Undertaker and the concerned citizen attempting to pay for burial of the Native American before the triumphant scene of Brynner and Mcqueen teaming together and braving snipers as they take the coffin up the hill.

In a way the misfit band assembled by Chris resembled the plight of the western movies that were coming to an end of their relevancy at least in their present form. At the start of the film Chris and Vin (McQueen) are struggling to find work as the more civilized the West is becoming, the less need there is for gunslingers like them. The rest of them are struggling to fit into this new world, their violent skills no good for the regular work some of them are trying (Bronson and Coburn), have left them mentally scared (Vaughn) or cynically suspicious (the other guy).

In what appears to be a lawless Mexico, our heroes get to thrive again and their skills once again become relevant. Somberly, it’s clear that once the evil has been driven out and the village, there is no place for our heroes. Four of them are dead, and the youngster of the group who is trying to follow in the other’s footsteps puts aside his gun and opts for a peaceful future and live in the village instead. Brynner’s line “Only the farmers won, we lost, we’ll always lose,” may be taken straight from Seven Samurai, but there is an added poignancy here with regards the mythic hero of the American gunfighter. The optimism and gallant heroism of the cowboy in cinema would within a decade be redundant in favour of the grittier, alternative anti-hero.

The entertaining, excitement and sheer fun of the Magnificent Seven made it one of the most enduring of all westerns. Three sequels were spawned, none of them frankly any good, a TV series and a recent remake which copied the original concept of having an all star cast headed by Denzel Washington and Chris Pratt. Funnily enough one of the most successful interpretations of the Seven mythos was not even a western but the Roger Corman Stars Wars ripoff Battle Beyond the Stars, which despite its cheapness is a fun ride and a wonderful homage to the original (it even has Robert Vaughn reprising the same sort of character he did in the 1960 film).

Why it always feels like Christmas though? I couldn’t tell you.

WTF? Why do I like this film so much?

If you have spent any time at all reading anything I’ve written about movies (and God bless you if you have), you’ll know that some of my tastes is way out there and some of the movies I’ve come to love are, well, odd. I’m grown quite comfortable not falling in line with critics or the general public when it comes to whether a film is “good” or not.

Yet there are times when even I have to look at a film and think: “why do I like this? and why do I own it on DVD?”

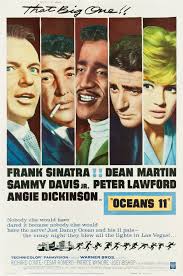

If you’re only familiar with the George Clooney, Brad Pitt Ocean movies, then let me explain that those films were based on a 1960 movie, where Frank Sinatra as Danny Ocean leads his real life chums “The Rat Pack,” on a heist to rob five Las Vegas casinos on New Year’s Eve. The film was a self indulgent mess, with Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jnr, Dean Martin and co using the production as an fully funded excuse to get together and party in Vegas. Filming was said to be chaotic with the cast turning up for filming when they wanted and for as little time as they could get away with, before hitting the bars and casinos again.

There’s little background to Danny and his crew, with very little motivation evident of what’s driven them to take on Vegas. the dialogue is cheesy and the plan itself is hardly inspired, in fact it makes robbing Vegas casino’s seem ridiculously easy. (And let me tell you putting a crew together an robbing a casino is not easy. The proof of that is the three friends of mine buried in the Nevada desert somewhere, and the two strippers we tried to use as lookouts, actually I feel bad about the strippers they were nice girls, and all we were trying to do was sneak out with the hotel towels.)

Yet I love that this movie exists. Why? I’m guessing it’s because as much as you can sense the arrogance and the ego involved in it, and as big a pain in the arse as I’m sure these guys were, it’s the bloody Ratpack together in a movie. The hopeless romantic in me just longs for a day when “cool” had a degree of class about it.

The immaculate suits, the classy lounge music, the fancy drinks, the exclusivity and comradery of the group and the sheer decadence of their lifestyle is just so delightfully enviable.

So yeah, so this film may be a glorified in joke and piss up session, along with being an obvious tourism advertisement for Vegas, but by God we get to hang out with the Ratpack for a few hours and that makes this film a win to me.

Ring-A-Ding-Ding

Salut

Dazza