The great thing about horror movies is that, by and large, they all secretly mirror what’s going on in society as a whole – in the process, bringing to light a lot of subconscious fears we have about modern existence. This was true, even in the silent film era – lest we forget pioneering works like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Nosferatu, which in an incredibly eerie manner, almost seemed to foreshadow the rise of post-World War I fascism almost two decades before Hitler rose to power.

From Frankenstein (rapid advancements in technology) to Night of the Living Dead (post-Civil Rights era racial tensions) to Friday the 13th (the Moral Majority and Reaganite social conservatism), horror films have secretly reflected our major worries and concerns about the real world swirling around us. Indeed, perhaps no other genre does such a remarkable job summing up the neuroses of the times; to watch and grasp the deeper subtext of horror flicks from any decade is to comprehend the collective mentality of the era.

And it’s for that reason – amidst an array of other problems – that modern day horror movies suck.

While there have been some good, if not teetering on great, flicks like The Babadook and It Follows coming out in the 2010s, for the most part it has been a terrible decade for genre pictures. For every halfway decent movie like The Last Exorcism and The Visit, there have been – no joke – at least 50 or 60 downright atrocious ones. And when I say atrocious, I don’t just mean bad, I mean practically unwatchable garbage with titles like Bury the Ex and Cadaverella.

While modern horror offerings may not reflect the hidden fears of U.S. society, they most certainly reflect the industry’s deep-seated aversion to original ideas. What scant genre offerings that have made it to cineplexes in 2016 have been your standard jumble of predictable, paint-by-numbers supernatural hokum – The Darkness, Before I Wake, Lights Out – and half-hearted, unnecessary re-dos, rehashes and remakes like Blair Witch, Ouija 2, The Conjuring 2 and yes, a remake of the barely 13-year-old Cabin Fever (which, in and of itself, was already a rip-off of about half a dozen genre classics.) Toss in boring, effortless “horror comedies” like Yoga Hosers and Therapy for a Vampire and hyper-overrated, pretentious bullcrap like The Witch and you have what very well could be the worst year for mainstream cinematic horror since the advent of the Internet.

The options off the beaten path are only marginally better. Granted, flicks like The Green Inferno, Cooties and Clown have their merits as good old fashioned degenerate cinema, but they nonetheless lack the artistic viscerality of genre totem like Halloween, The Evil Dead, Re-Animator or The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Rather, these films seem so hung up on imitating the classics of eras gone by that they never make an honest effort to claim a unique identity or make any sort of profound sociocultural observations of their own.

Throughout the history of the horror film, only two types of genre movie have ever proven to be successful: those that throw caution to the wind and do everything they can to not only shock and offend audiences but make them physically ill – a time-honored motif that runs all the way from Salvador Dali’s Un Chien Andalou to The Human Centipede 2 – and those that make an honest attempt to capitalize on some sort of collective fear buried deep within our psyches, even if it is something as rudimentary as our basic fear of mortality. Meanwhile, the absolute best of the best – your Exorcists, your Dawn of the Deads, your Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killers – strive to do both.

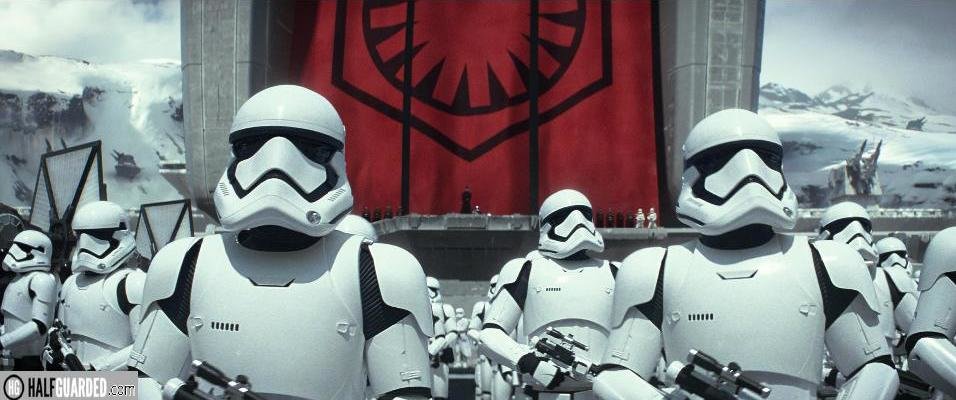

With a few noteworthy exceptions, the horror flicks of the 2010s have been hesitant to ape either of the above-mentioned formulas for success. For one thing, after a decade of Saw and Hostel “gorenography” – not to mention a steady diet of weekly, extremely graphic (and extremely sexualized) violence on HBO programs like Game of Thrones – it’s virtually impossible to shock audiences with standard splatter movie blood and guts anymore. Secondly, with the dual rise of neo-political correctness and social media, it’s difficult to even promulgate the idea of a collective psyche existing anymore. How are you supposed to strike a nerve, exactly, when everybody’s collectively balkanized and individually “triggered” by even the slightest of trifles?

Today, we are a global society utterly terrified of expressing our true feelings. In our always-online, social media mega-sphere, we pretty much have to self-censor, as a form or cultural survival. After all of that worrying about Big Brother, at the end of the day, it was the general public that drove us into a state of chilled silence and nonstop paranoia. In short, it is the absolute perfect fodder for the next wave of horror movies – films in which the great terror is not losing your life, but losing your core identity, your ability to detach yourself from the herd mentality and to be your own person.

What’s the point of being afraid of zombies and werewolves when one errant tweet could cost you your job, your livelihood, your house and your children’s future? Furthermore, why should we care about witches and ghosts when we’ve got real world terrorists and mass shooters to worry about – who, for all we know, could be living next door to us right now? In the 1950s, horror films reflected the fear of atomic technology. Today, our great technological fear doesn’t stem from the prospects of irradiated mutant insects eating Cleveland, but from the dissociative effects of the Internet turning us into either a bunch of like-minded mush heads or severely alienated lunatics.

Granted, there have been some movies that have attempted to tackle the concept – VHS, Unfriended and to some extent, even the [REC] movies immediately spring – but by and large, these flicks are trapped by the whole “found footage” premise. They exist only as their gimmick, and thus, never really burrow into the marrow of the true societal terror they wish to comment upon.

Enter the future of the genre, folks – “the social horror movie.”

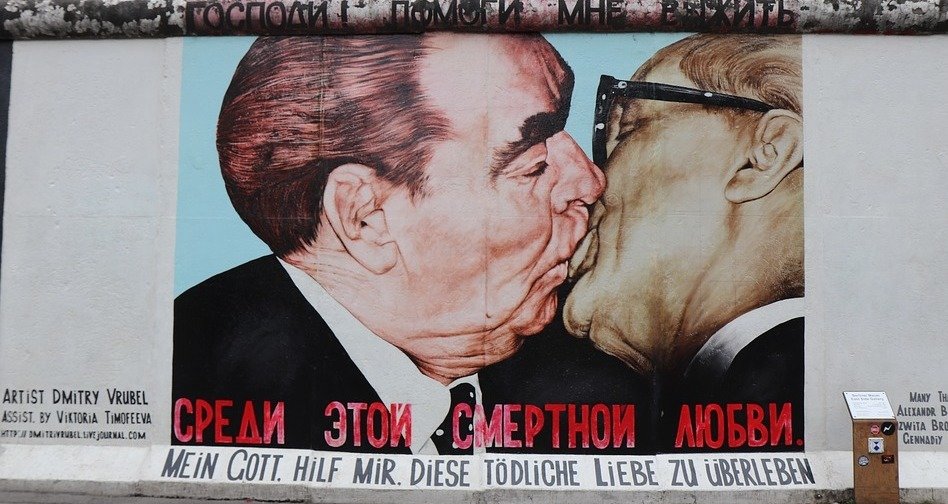

Granted, horror movies touching upon the fear of cultural impositions are nothing new (indeed, silent movies like The Golem and Haxan directly addressed then-contemporary social anxieties, such as anti-Semitic persecution and the utter and complete lack of effective mental health treatments.) But over the last decade, we’ve seen a notable uptick in horror films that contain profound sociopolitical commentary, to the point that the films themselves could more or less be considered allegories for our shared post-globalization fears.

With graphic, pioneering ‘70s films like Salo, Caligula, The Devils, In The Realm of the Senses and Cannibal Holocaust laying out the template, the “social horror” movie of the 21st century is explicitly, intentionally violent and sexual in nature – sometimes, incorporating real scenes of intercourse and splicing actual footage of death and dismemberment inside the “fictitious” film narratives.

Two of the best examples are 2006’s Taxidermia and 2010’s A Serbian Film – incidentally, two films hailing from the former Soviet bloc states in Eastern Europe. The former is a film that directly homes in on the sociopolitical trepidations of the masses, painting a portrait of modern existence that’s just as vapid, ambitionless and ugly as life under fascist and communist rule, while the latter is a flick about a retired adult film star offered an insane amount of money to star in some really, really perverted features. Add to that list a series of extremely graphic, no-budget shockers like The Angel’s Melancholy, the August Underground trilogy and the entire filmography of Lucifer Valentine (be forewarned, he mentions upfront his oeuvre is inspired by a bizarre love of vomit) and one bears witness to the natural progression of the horror film as an artistic reflection of culture. Yes, it is gruesome and nasty and stomach churning, but it is no longer a celebration of fantastical violence coiled around predictable supernatural hokum or smarmy, self-reflexive humor. Instead, it’s the retransmission of violence in our actual world, of the abuse and carnage and horror that reigns supreme in the shadowy recesses of our inner cities and the darkened corners of our suburban and exurban strongholds.

This is the great post-post-post-modern collective fear: that although we are aware of violence everywhere thanks to the advent of the Internet, we nonetheless feel supernaturally safeguarded from that violence ever happening to us. We’ll never get mowed down in a mass shooting. Our kid will never get abducted by some psychosexual maniac. We’ll never get blown up in a terrorist attack. We’ll never get shot in the back of the skull during a “routine” armed robbery. We’ll never get gangraped behind a dumpster. I mean, these things definitely happen, but thanks to some magical totem, we’ve convinced ourselves that all-too-real horror will ever befall us.

But we know it’s there. Indeed, all it takes is a few clicks on the Internet and we’re at Liveleak or WorldStar HipHop, watching the pain and suffering and torment and torture and sometimes deaths of others as entertainment. We all like to pretend we’re above such prurient pursuits, that we’re much nobler savages than that, but we aren’t. We like to gaze in the abyss, just as long as the abyss never looks back at us.

THAT is where the next wave of horror movies needs to go. Right now, we’re all a bunch of gawkers and lookie-loos at the zoo, admiring the beasts from afar, knowing full well that the cage separating us from the primitive spares us from bodily harm. U.S. culture works in much the same way, albeit, with a steady Internet connection representing the electronic bulwark segregating the collective id from the collective ego. But what happens when the social facade breaks, and the whole world can see our inner vileness and ruthlessness, while at the same time, our individual weakness and powerlessness is broadcasted to the world at large?

“In space, no one can hear you scream” was the brilliant tagline for Alien. Perhaps a modernized spin on that sales pitch should be horror’s new rallying cry.

Outside of cyberspace, no one cares if you scream.

Comments 2