What is this place? It’s so weird and unsettling, frantic and bombarding my senses with new stories. What happened to Comic Conversations? What is Halfguarded? Where are my boys? Fettman, Luro and Marvel2k? Who is this maniac in charge? And what is all this talk of fights in cages?

This is chaos…I think I like it. I may stay.

It’s 1990 and I’m reading the first issue of a UK comic strip anthology, published by Marvel UK though you’ll be hard pressed to find any indication that the house of ideas are behind it. It’s a comic designed to tap into the craze for “mature” content that is suddenly making the genre relevant to a whole new audience. The main strip is a reprint of a comic from Marvel’s creator owned epic line and frankly it’s blowing my mind. I’ve been aware of a new breed of darker superheroes for sometime, but this is something different all together. This is a complete pisstake of the genre.

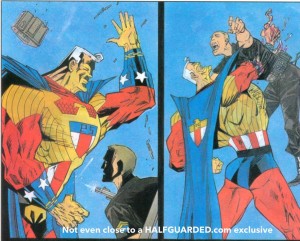

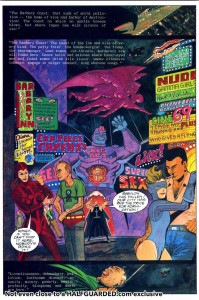

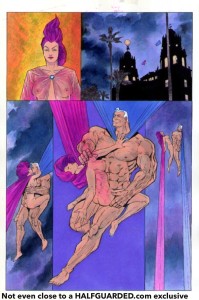

In the eleven pages of the first instalment we see a hooker in a superhero outfit, brutally assaulted and murdered by the terrifying “Sleepman” a cloaked figure with a bag over his head. A failed superhero (his attempt to be granted superpowers only resulted in him growing a monkey tail) is almost lynched for the crime by a vigilante gang, their leader “Sucicda” wears a necklace of severed ears. A rescuer comes flying over what looks like a superhero themed brothel, at the time I’ve never seen such overt sexuality in a comic. When he arrives he’s even more vicious looking than the villains we’ve already met.

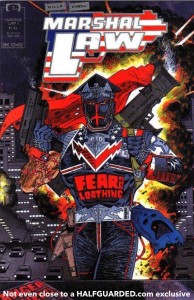

“I hunt heroes, I haven’t found any yet” is his unforgettable tagline and we’ve just met Marshal Law, his costume a hybrid of a police uniform and bondage gear.

When talking about the comic boom of the late 80’s and the whole inverting of the superhero genre, Marshal Law is largely forgotten. It was definitely an adult book and ground breaking in it’s own way but it didn’t court the critical or intellectual acclaim of Watchmen, Dark Knight and Killing Joke. Those comics were distancing themselves from the regular superhero genre (Moore has insisted that Watchmen is not a superhero comic), tackling themes that had not been seen in comics but Marshal Law was actually about superheroes comics themselves.

Created by the British team of Pat Mills and Kevin O’Neil for Marvel’s Epic line, Marshal Law was originally meant to star in a Mad Max style post apocalyptic landscape. However as they waited for Marvel to get going on the series the Dark Age of comics arrived and Pat Mills had the idea of switching him into a superhero story, but as Mills hated Superheroes and the values they represented he’d be a superhero hunter given him the chance to ridicule and satirise everything there was to do with the genre.

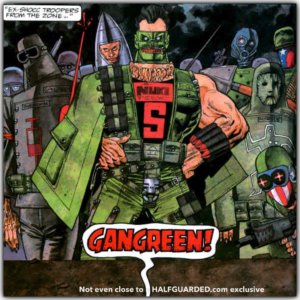

Marshal Law polices a San Francisco devastated by the big earthquake, it’s ruined streets ruled by gangs of vigilante “Superheroes” most of them veterans of a Vietnam style war in South America known as The Zone. Following the war most heroes are dubbed as “surps” (surplus heroes), outcasts living troubled lives and many destitute. While others live a hedonistic, celebrity lifestyle loved and worshipped by the masses such as Marshal Law’s chief suspect in the Sleepman murders, the ultra patriotic symbol “Public Spirit”.

Public Spirit represents the old school, idealised superhero at least on the outside, his public persona embodies Captain America and Superman. This is the same hero stereotype that the tide at the time seemed to be turning against in favour of the violent, gun touting anti hero. Looking back this conflict between Spirt and the Marshal represents that shift and in many ways the first six issue series represents what could have been a change in the whole superhero genre.

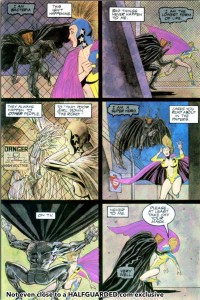

It’s clear that Mills is venting his hatred for superheroes. Just as he has the Marshal giving a beating to the heroes on the page, Mills gives repeated kicks to the bollocks of the whole genre and what it represents. The frustration with the portrayal of women is plain to see (Mills was heavily involved with the once lucrative girls comic scene in the UK) with obvious parodying of the revealing outfits the female heroes generally wear, especially when it comes to the explicit outfit the Spirit’s girlfriend Celeste wears. She Beast is also worthy of mention as she plays the role of the powerhouse female but inverting the character to a heavyset, steroid using bodybuilder, mocking the need to always feminise such a character in the superhero universe. Likewise the male heroes all have impossibly huge, exaggerated physiques, which ironically would become even more so in the comics in years to come.

There is so much to devour in Marshal Law in it’s satire on the genre with regards the sexual fetishism of the heroes, the deity worship and their role both sanctioned and vigilantes as jackboots serving authority. The comic practically welcomes such analysis through Lynn the girlfriend of Law’s civilian alterego. She’s a radical, angry student activist with a particular hatred for heroes and her essays highlight what she sees as their misogyny and fascism and unworthiness as role models. She also has a knack of seeing phallic symbolism within superhero imagery and dialogue.

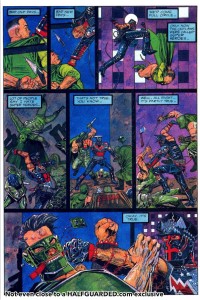

There is a lot to enjoy beyond the satire, there is also a lot of black humour within the series. Some of it crude and gory, other times downright disturbing, such as the scene where Hitler Hernandez kicks a child off into the distance like a punted football.

Also worthy of note is the artwork by O’Neill. What I love about it is the detail that is given to ensure every superhero costume looks unique and you can imagine as being a career long hero, even for those that appear for a single panel.

I only came to write this article when researching Pat Mills for some of my other articles. The truth is, I’d forgotten about Marshal Law, as I’d subconsciously classed it as a “Not aged well” book. I think I was prejudiced by how Marshal Law was handled after the initial six issue series. Marshal Law continued in a series of one shots which focused more on the slapstick and gore humour. The satire of the series was replaced more by direct send ups of specific superheroes such as the Batman parody in Kingdom of the Blind and the Punisher and rest of the Marvel universe in Marshal Law takes Manhattan. They’re entertaining and still funny, but lack the subtlety and intelligence of the first series. O’Neil’s artwork also becomes cruder and more cartoonish departing from the vibrant work in the original.

Marshal Law appeared as the main strip in the short-lived UK anthology strip Toxic in a zombie storyline that didn’t do a lot for me and my interest in the character waned and I moved on. The Marshal’s future sporadic appearances consisted mostly on teamups with the likes of Savage Dragon, Pinhead and The Mask.

It’s a shame because I feel there was so much potential beyond the extreme humour (Mills admits it got to the stage they were trying to see how much they could get away with). The themes of American interventionism, media control and a celebrity obsessed culture which were touched upon in the first series have become even more relevant since the initial publication.

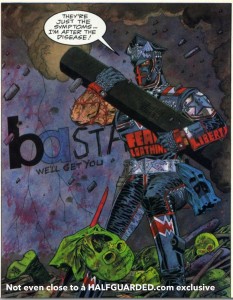

The Marshal’s character is also severely underused in the follow ups, as he had a complexity beyond the violent hero bashing that he is often known for. Although he admits to enjoy the beatings he hands out to the supes he purports to hate, he allows them to escape from battles rather than pursue and finish them off, stating “ they’re just the symptoms, I’m after the disease.”

There’s more hints of a compassionate side when he goes through the humiliation of publicly speaking in support of the Public Spirit in order to secure a large donation for a refuge for down and out super heroes. This is particularly painful as it’s the Spirit who he blames for the propaganda that led to him and so many others signing up to serve in the Zone. It’s this hatred that blinds him into believing he is behind the Sleepman murders (the revelation behind the Sleepman are a great twist and the hints are there all along).

As well as seeking vengeance for what he believes is a betrayal on him and all those who fought in the Zone he also seeks atonement after having his eyes opened by Lynn as to America’s role in the war. In one of Lynn’s essays she speculates that the barb wire on his costume represents a need to be punished for past crimes. You get the sense that the Marshal is trying to do some good, (the job he has is as a hospital orderly) and when he debates superheroes with Lynn he asks her how she feels about the Marshal policing the heroes (Lynn doesn’t know he’s the Marshal). Her reply that he’s the worst of them all draws a hurt look on his face, dismayed at the thought he’s no better than those he’s hunting (although later he does say he can live with with being called a “glorified Nazi, with a pathological hatred of superheroes, revelling at the chance to beat the hell out of them”).

Rereading the Marshal Law comic for this article I realised it is a very bleak book. Compared to the positivity of the conclusion of Dark Knight and the ambiguous one of Watchmen, Marshal Law ends on an absolute downer. Despite the defeat of the Spirit and the realisation that no one can live up to the standards set for the superhero the whole incident will be covered up. To the Marshal’s disgust nothing will change, he’ll continue to police the heroes only picking at the symptoms forever more.“We have to believe in the myth of the superhero. Reality—is too much to bear.”

It’s as if Mills knows that as much as he highlights everything which is wrong with the superhero, they’re not going away. Today they’re bigger than ever, going beyond comics into dominating films and television. They may be more sophisticated in terms of storytelling and artwork and have gone some way towards diversity in race, gender and sexuality but when you see a cover of a Hawkeye comic with Mockingbird’s costume disappearing up her arse you realise that there are areas that Mills was attacking that are still prevalent in comics today.

Marshal Law did make me question the values expressed superhero comics with regards violence, the objectification of women characters and unrealistic body standards it promotes.

But did it change my reading habits?

Did it Bugger.

The majority of comics I buy and collect are still superhero ones. Ask me to name my top 100 comics or storylines, I’m betting most of them are superheroes. And although I take the points that Mills raises regarding the sexual imagery that is rife in superhero comics and recognise how ultimately unhealthy it may be, I have to admit I still find the outfits of Blackcat, Spiderwoman and Ms. Marvel extremely hot.

Marshal Law is something I’m so glad I revisited, because there is a lot more under the surface than a simple piss take on superheroes. Read for yourself and see what you can make out of it, because lucky for you a Hardback edition of most of Marshal Law’s work came out a few years ago.

Til Next time

Dazza

By the way, If you enjoyed this article and want to read more (like you have a lot of time on your hands or something) then check out my previous articles on comic conversations old site. I cover a mixture of subjects, ranging from the well known to cult classics including a series on some of the best British comics that I grew up with.

Enjoy.

FUCK. YES.