This article is about how to act if you are in a situation with a friend or family member known to have mental illness and that person is melting down. This is not an instructional on how to be a vigilante psychiatrist. I’m only referring to situations where you KNOW the person. If you don’t know the person or it seems dangerous, do not get involved. Call for help! NONE OF THIS IS MEDICAL ADVICE!

So I had a bit of a meltdown… Ok, it was a total meltdown. If you’ve seen one, you already know.

For those who don’t know, I have a few screws loose in my brain, but that’s ok, many of us do. About 18 percent of the total adult population in the United States suffer from some mental illness, or enduring condition such as depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia. This group includes Coughlin and I. That’s probably why you like this site so much.

Anyway, for the purposes of this article, I’m using the term “meltdown” to mean a situation where a person is freaking out hard. I’m broadly referring to any tense scene where someone is out of control and you’re not sure how to handle yourself. In this scene, danger isn’t necessarily imminent, and we’d like to keep it that way. There are always two roles. I’m playing the part of the crazy (me), and you are playing the part of the sane (you). What does that script look like?

If you ever encounter a meltdown scene, the first thing to remember is that the person involved is not thinking. They can’t think. So you’ll have to think for them. That doesn’t mean doing or saying anything yet, just start paying attention.

Personally, my meltdowns consist of uncontrollable sobbing brought on by an unrelenting feeling of despair. Often I get so far down the hole that I become delusional and say irrational things. I can be pretty mean and insulting, so please ignore my parlance as well. My most recent episode was capped off with my demand to speak to Dr. Drew because I thought he could help me (I still think he can). For those of you that follow me on twitter (@PeachMachine), you may have noticed my rapid fire tweets. I apologize (but I really would like to talk to Dr. Drew so tweet this article to @DrDrew & @DrBruceH just in case Drew breaks his lenses). This article is about how to deal with someone around you having a meltdown. I hope Dr. Drew approves.

I recently listened to Invisibilia, episode 6: The Problem with the Solution. It’s a podcast from NPR. The topic was mental health, specifically about how families deal with it. It gave a lot of good examples of how people think they should deal with someone in the throws of a meltdown. It talked specifically about how people try and STOP the behavior or the person mid meltdown, which never works. It’s too late for that.

Most think the solution to the problem of mental health is to just force people into “acting normal.” “Stop that!” “Give me that.” “Don’t touch that.” “Look at me.” “Stand still.” “Be quiet.” They think that if they make the person just do normal stuff, that makes their illness go away. It does not. Let me explain…

Regardless of my recent meltdown, my depression and other whacky issues are reasonably controlled, but sometimes I do odd things that make no sense to you. I organize stuff. I put things into rows and columns and count things. My desk has 75 paper clips in the top left section of the middle drawer. Don’t fuck with them. Sometimes I need to do this.

Sometimes I need to scream and tear my clothes off. Sometimes I need to twist all the buttons off my shirt. It’s not your job to stop me because it’s not normal behavior, it’s your job to put the buttons back on so I can do it again. Be aware of behaviors that seem odd to you, but don’t necessarily try to stop it. Yes, I may be needlessly alphabetizing old magazines, or color coordinating my t-shirts by drawers, or taping paper with scribblings on it to a wall. That’s me handling my own mental health. It’s no different than people who spend hours gardening or painting a home. It may seem unproductive, but it’s not to me. Planting bulbs is your therapy. Organization is mine. Why would you try to stop that, only because you don’t understand.

I love counting change. I love it. I may be totally focused. Don’t attempt to intervene. YOU screaming at me to snap out of it, will do nothing but push me over the edge. There can be physical or verbal cues that people will give you before a meltdown begins, so ask that person what the signs are so you can be aware. I NEED to count change and stack all the pennies into piles of 10 and then roll them. Don’t confuse the behaviors that help for warning signs. I could make a list but everyone is different, so talk to the person first.

If I’m going to meltdown, I’ll give you signs. First, I’ll get disorganized. If I stop putting my stuff away and begin leaving stuff on the floor, or if things start to seem messy, that should tell you, my brain is slipping into messy mode. Frustration is next. Nothing seems to be going right. After that, it’s anger. Next is the meltdown.

I first get this hyper-focus, which leads me to think completely irrationally. I start breathing hard. Everything bothers me. I don’t know why this happens. A short circuit in my brain is how I understand it. I know it’s just going to occur sometimes; it’s inevitable. Thus, I have some strategies to keep me from melting down (they usually don’t work past this point). So while I may have a few tricks up my sleeve to stop it, I can still easily get to meltdown mode quickly, and if the people around me do not know what to do, it can exacerbate the problem.

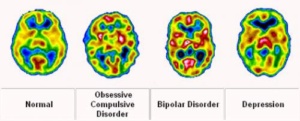

Let’s be clear. This is not the type of illness that goes away with a few trips to a therapist, or after taking Prozac for a month, or a phase one can grow out of or simply switch off. It’s a wiring issue. Our brains are wired differently. Families and friends need to understand:

- It’s not sadness; it’s depression.

- It’s not a single issue; it’s a chemical imbalance.

- It’s not really an illness at all; it’s our genetics.

Here are answers to some common questions people may have about mental illness, in real life terms, from my perspective. This is not medical advice, just my personal opinion and insight based on what has worked with me, and what I’ve observed working with others.

Common questions to people with mental illness:

Is your brain different than mine?

Not really, but it works differently (see above). I mean, sure, I’m waaaaaay smarter than you. I actually have a 131 point IQ which is right at MENSA level, but you’d think I was 9-years old if you saw me melting down. My point is that mental illness can affect anyone.

Everyone’s brain is slightly different, but for the most part, people respond similarly in most situations. This is not the case for those with mental health issues. Sometimes we have an extreme response to a common experience, usually something another person would not even notice, like someone whistling. Often the cause of the meltdown appears to be something trivial, but what you won’t know is that it was the last thread to pop on a day of barely holding the seams together. Now I’m having a meltdown and it appears that it was over literal spilled milk… it is not.

Can you feel a meltdown happening?

I can. I don’t know about others, but usually there are signs. Ask the person beforehand so you know.

Personally, I feel my brain change from normal function to something else, just out of nowhere. It’s like an old TV set with rabbit ears antennae. Usually the picture is clear, but sometimes it gets scrambled, for no good reason. It’s not like the TV moved spots. You turned it on just like normal, and there’s no picture, just a weird blur. You can’t explain it, but there IS a reason. Something is interfering with the signal, but you can’t detect it. That’s what happens in my brain.

Can you hear what I’m saying while it’s happening?

Maybe, but it’s not important. During a meltdown, my brain is scrambled. My signal is messed up and I’m all over the place, overreacting, and melting down.

I’m not listening to you anyway, so don’t try and figure anything out. Say very little, and please stop yelling my name! It’s probably already loud. Don’t add to the decibels. At this point I’m not interested in a solution. Let me get it all out.

What is likely to happen?

Anything, but it won’t be directed at you. I thrash on the ground, I feel like I’m about to burst into flames, I wale and sob uncontrollably. It’s horribly embarrassing because nothing is really wrong.

To an outsider, you’d like think I was insane, or at the very least, just found out my family was murdered. Since this isn’t true, I must be insane. But actually, I’m neither insane nor violent. In fact, I’m usually quite normal. My friends and family understand this and thus don’t have to have me 5150’d (an involuntarily confinement of a person suspected to have a mental disorder that makes them a danger to themselves or to others) during a meltdown. This is why it’s important to talk to the person BEFORE it happens.

How long could it last?

Unknown.

My episodes usually last a couple hours and then I fall asleep, and wake up with little memory of the specifics about what occurred. I always remember the beginning but never the end. That’s me, not everyone. Sometimes I can kick out in 15-minutes. Sometimes it is all day.

What do we do after?

I don’t want to talk about it. I’m definitely embarrassed, and I’m definitely not looking to accidentally trigger myself back there. So let’s not talk.

The following is from a friend who personally has handled me on more than a few occasions. She’s been very successful in doing so as well and this is her advice, I paraphrased it a bit:

Sometimes, when it’s all over, the person who was witnessing it feels tremendously guilty and anxious about their own part in the situation. (Believe me, I feel incredibly guilty for putting you through it.) For me, the “after” is sometimes more difficult than the actual moment. After it’s over, I realized that I just needed to be there which means LISTENING. It does not mean I need to give advice or talk about my own personal experiences. Offering suggestions or strategies that may have worked in the past could be helpful, but there is typically a better time and place for that (i.e. tomorrow). This is the most difficult part. I know what helped last time, I know what will happen when it’s over, but in the moment it can be hard for ME, the sane, to reason or think as well. I head to learn to be comfortable with silence and be patient.” (And thanks for always making me smile ;-))

I’ll let you know when I’m good. So just go about your business. Move along. These aren’t the droids you’re looking for.

Is it my fault?

No. It’s nobody’s fault, but as I’ve experienced, after a meltdown, both parties feel incredibly guilty.

I would also suggest that at some point, YOU need to take care of YOU. Being close to someone who experiences a mental health crisis is emotionally draining. It’s just as important for the family member to talk with someone, seek support, and make healthy choices. Debriefing with someone you can trust after a stressful moment is recommended for sure. I can’t hold it all in, and thus the meltdown, but you’re not responsible for taking my pain away. If you’ve had enough, take a break. YOU don’t have to do it all.

Give each other some space. As long as your heart was in the right place, I’m sure all will be forgiven even if you caused it. That said, let’s not make it worse by casting blame.

SUMMARY

In this article you learned what a meltdown may look like. Many people do more harm than good interfering with a meltdown because they don’t realize what is happening. Their heart is in the right place, but their head didn’t know the best response. I’ll talk more about inappropriate responses in part 2, as well as get into more of what I learned from the Invisibilia podcast.

Living with someone prone to meltdowns is not easy. You have to know what to expect before it happens. You need to know what can or should be done. Usually less is more. It’s the responsibility of the people around to know. Do not expect the person in the throws of the attack to respond informatively. Don’t get your feelings hurt, and don’t get mired in trying to figure out the “why.” It doesn’t matter right now.

When dealing with a situation like this, If you remember nothing else, think about being harmless instead of helpful. Let’s do no harm, and help later.

@PeachMachine

From PositiveMed.com…

The following symptoms are not an absolute guide and if you find yourself or a loved one behaving erratically or drastically different than they have been or losing all interest in things they once found fascinating, it may be time to see a therapist or at least a family doctor. If several of these indicators are occurring, a serious condition may be presenting itself:

• Loss of interest in others and social withdrawal (THIS IS THE MAIN ONE!!!)

• A drop in interest/functioning/ability at school or at work with such indicators as failing a class, quitting a sport without prior notice, or difficulty performing tasks

• Difficulty concentrating; difficulty forming logical thoughts, speech, or memory

• Heightened sensitivity to light, sounds, touch, or smell; avoidance of crowded or loud situations

• Apathy, loss of initiative or desire to be social or participate in activities

• Vague feelings of being disconnected from one’s surroundings or oneself

• Illogical, “magical” thinking that’s typical in childhood being present in an adult

• Exaggerated beliefs or unusual beliefs about personal powers or connectedness to a religious figure or celebrity; personal belief in powers to understand subtextual meanings or the ability to influence events

• Heightened anxiety or nervousness

• Unusual fear or paranoia about other people and their motives

• Peculiar, uncharacteristic behavior

• Rapid or dramatic changes in feelings; “mood swings”

• Dramatic change in sleep and appetite or deterioration of personal hygiene.

Again, one or two of these symptoms cannot predict a mental illness. However, a person experiencing several of these symptoms together to the point where it is hindering their ability to work, study, or relate to others should be seen by a mental health professional.

Comments 2