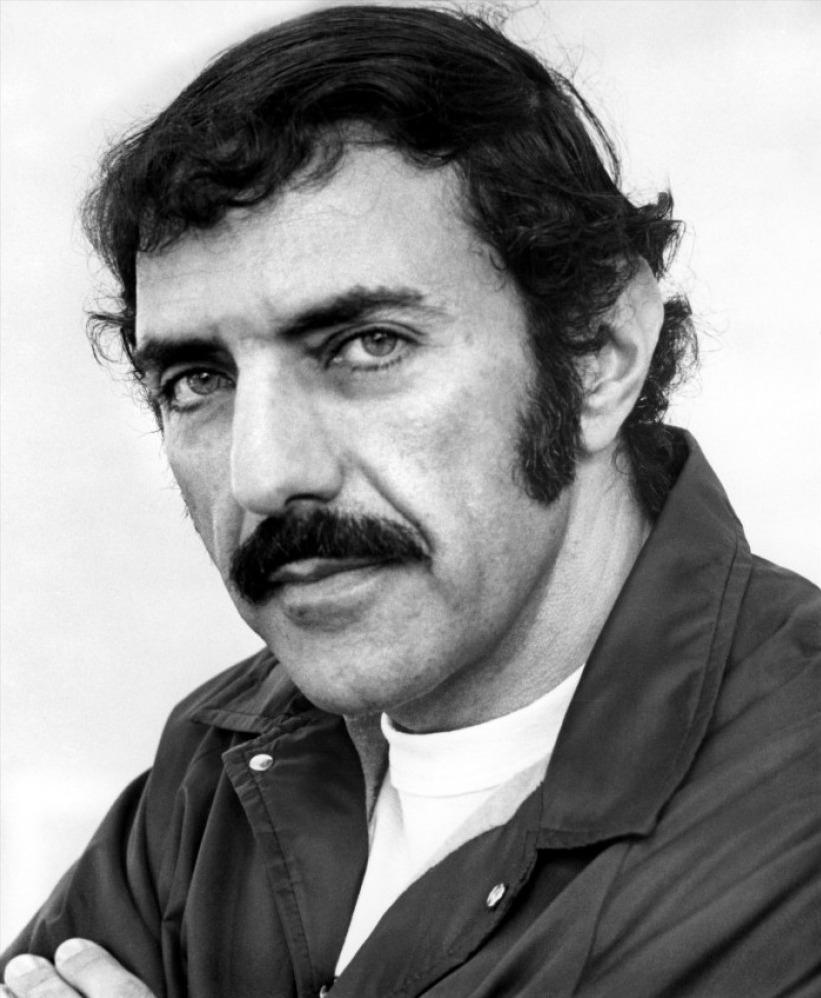

Most writers in Hollywood consider themselves extraordinarily lucky if they create a work that’s truly timeless.

William Peter Blatty, who died at the ripe old age of 89 on Jan. 12, managed to crank out three.

Taken as a whole, Blatty’s trifecta of The Exorcist (1973), The Ninth Configuration (1980) and The Exorcist III: Legion (1990) – all three of which he scripted and the latter two he directed – has to be the greatest trilogy in horror film history. While each film is wildly different, each also addresses the same core themes: the frailty of man, the mysteries of death, and most importantly, the eternal struggle of good against evil. With post-Hippie idealism and academic moral relativism already beginning to supplant the old Judeo-Christian norms as American society’s guiding moral precepts, Blatty – himself a devout Catholic – sought to bring cinemagoers the most counter-cultural message of all: a big, fat dose of New Testament duality.

So much has been written about The Exorcist – a film regarded by many critics as the absolute greatest horror film ever – that it’s hard to overstate its impact not only on American cinema, but U.S. society as a whole. Every blockbuster makes the claim, but The Exorcist truly was a cultural phenomenon – a movie that shook people to their very core, an experience so intense some viewers were driven into the throes of hysteria. But what really impacted moviegoers wasn’t the projectile vomit and the crucifix masturbation – it was the straightforwardness of Blatty’s good versus evil narrative. In the age of pop nihilism, where the only cardinal virtue was “if it feels good, do it,” Blatty’s film’s had the audacity to declare, rather boldly, that humanity was caught in the middle of a spiritual war between a supernatural goodness and a supernatural vileness. The darkness in Blatty’s film wasn’t the kind of self-directed ennui and dissatisfaction that films like Easy Rider and Last Tango in Paris told us could be overcome by a steady diet of pharmaceuticals and anonymous romantic partners. Blatty’s demons struck at something much deeper in the human condition. While other movies dwelled on the pangs of postmodernism, The Exorcist hinted at a primordial presence, a figurative and literal devil that has rested on man’s shoulders since the dawn of the species.

Even now film analysts banter back and forth whether The Exorcist is ultimately more Blatty’s film or more director William Friedkin’s. Of course, the film itself is based on a novel written by Blatty, who also penned the film’s screenplay, so it’s fair to say – at the very least – he deserves co-authorship credit for its success. Interestingly, there are some key differences between Blatty’s book and Blatty’s film – the most interesting, perhaps, being the cinematic omission of an “evil book” which calls into question the authenticity of Regan’s possession – but both the novel and the movie convey the same central message. “I think the demon’s target is not the possessed, it is us, the observers, every person in this house,” the elder priest tells his doubting apprentice in a pivotal scene in the book that was initially left on the cutting room floor. “The point is to make us despair, to reject our own humanity … to see ourselves as ultimately bestial, as ultimately vile and putrescent, without dignity.”

That’s an idea that’s hard to escape in the introduction of The Exorcist, where Blatty lists the Holocaust bodycount and a handful of mafia torture tactics in graphic detail. The horror of Blatty’s works isn’t in pinning some kind of supernatural scapegoat on the failings of man – rather, it’s taking the totality of mankind’s destructive, inhumane transgressions and displaying it as a supernatural force in and of itself.

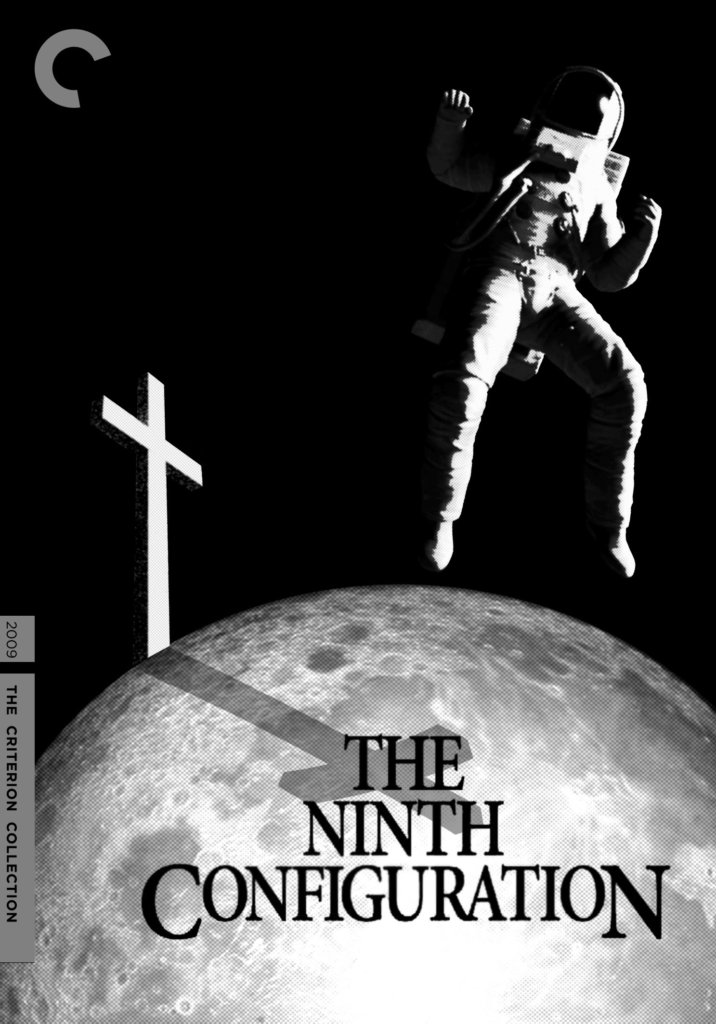

But to counter that horror, Blatty’s work also focuses on an antithetical beauty. Human beings in Blatty’s films aren’t powerless against the forces of darkness. Indeed, in all of Blatty’s works, the goodness of humanity – our selflessness, our altruism, our basic decency – always prevails. That’s a message viewers of The Exorcist seemed to miss. Father Karras’ death at the hands of the ghastly ghoul that possessed Linda Blair wasn’t a “win” for the unholy empire – rather, his messianic sacrifice was meant to symbolize a perfect love and goodness that triumphed over evil, ultimately saving Regan’s soul in the process. The public consensus that the devil “won” in The Exorcist – in tandem with the trainwreck that was The Exorcist II – drove Blatty to direct his own spiritual sequel that would more firmly express that “good triumphs over evil” dynamic. The end result was 1980’s Ninth Configuration, an adaptation of Blatty’s pre-Exorcist novel Twinkle, Twinkle Killer Kane.

While not a horror film in the traditional sense, The Ninth Configuration certainly proves a better follow-up to The Exorcist – qualitatively and thematically – than its atrocious official sequel. Here, writer and director Blatty crafts a truly unique black comedy, in which a gaggle of high ranking military officials all experiencing psychiatric breakdowns – including the astronaut from The Exorcist – take refuge in a top secret retreat in the Pacific Northwest, where top Vietnam colonel Kane suggests letting the inmates literally run the asylum is the best therapeutic tool. Of course, the film does have something of a supernatural bent to it – or rather, a decisive psychological thriller component – but alike The Exorcist, it is ultimately a film about faith. With all of the madness (literally) running throughout the castle, the primary plot of the movie concerns Kane’s feeble attempts to convince the AWOL astronaut that a benevolent higher power exists. If The Exorcist was a film about finding Satan through insanity, The Ninth Configuration is a perfect bookend – a film about finding God through insanity.

Which makes The Exorcist III: Legion – yet another film directed and scripted by Blatty, based on one of his earlier novels – something of a syncretism of The Exorcist and The Ninth Configuration. Very much a horror film in tone and intent, it too stresses the vileness and ugliness of human evil – this time, via a psychotic murderer instead of a demonically infested child. Alike The Ninth Configuration, however, the film does attempt to express the primacy of a higher moral good – a facet of the movie embodied by the appearance of Father Karras’ spirit and George C. Scott’s impassioned spiel in the final “exorcism” sequence.

Taken as a whole, Blatty’s cinematic trilogy is unquestionably the most introspective of all marquee “horror” series. Blatty’s films are about much more than the devil and the fear of being murdered – rather, his trifecta is about the very nature of humanity, exploring both its most altruistic and destructive poles. His films are every bit about redemption as they are condemnation, with each film demonstrating the duality of human actions. We can be demons and we can be angels – and sometimes, both at the same time. The philosophical complexity of Blatty’s works are practically unparalleled in the genre, and even compared to the heaviest of heavy hitters in world cinema – Bergman, Kobayashi, Pasolini, etc. – the “unholy trilogy” remains some of the most thought-provoking, soul-stirring films anywhere, at any time in cinema.

While many filmmakers and screenwriters have no clue but as to guess what their lasting legacy will be, Blatty cemented his a long, long time ago. Making just one great, genre-transcending film is enough to go to your grave happy – and with The Exorcist, The Ninth Configuration and Legion all on his resume, I think it’s safe to assume Blatty’s going to be smiling from here to eternity.