My hometown is Panem. No, literally: the very small, suburban Atlanta town I grew up in will be the site of a multi-million dollar theme park, set to open in 2019, which will feature, among other things, a simulacram of The Hunger Games experience. (In case you’re wondering, the other big attraction is some kind of interactive experience modeled after the Step Up movies. Move over Harry Potter World, am I right?)

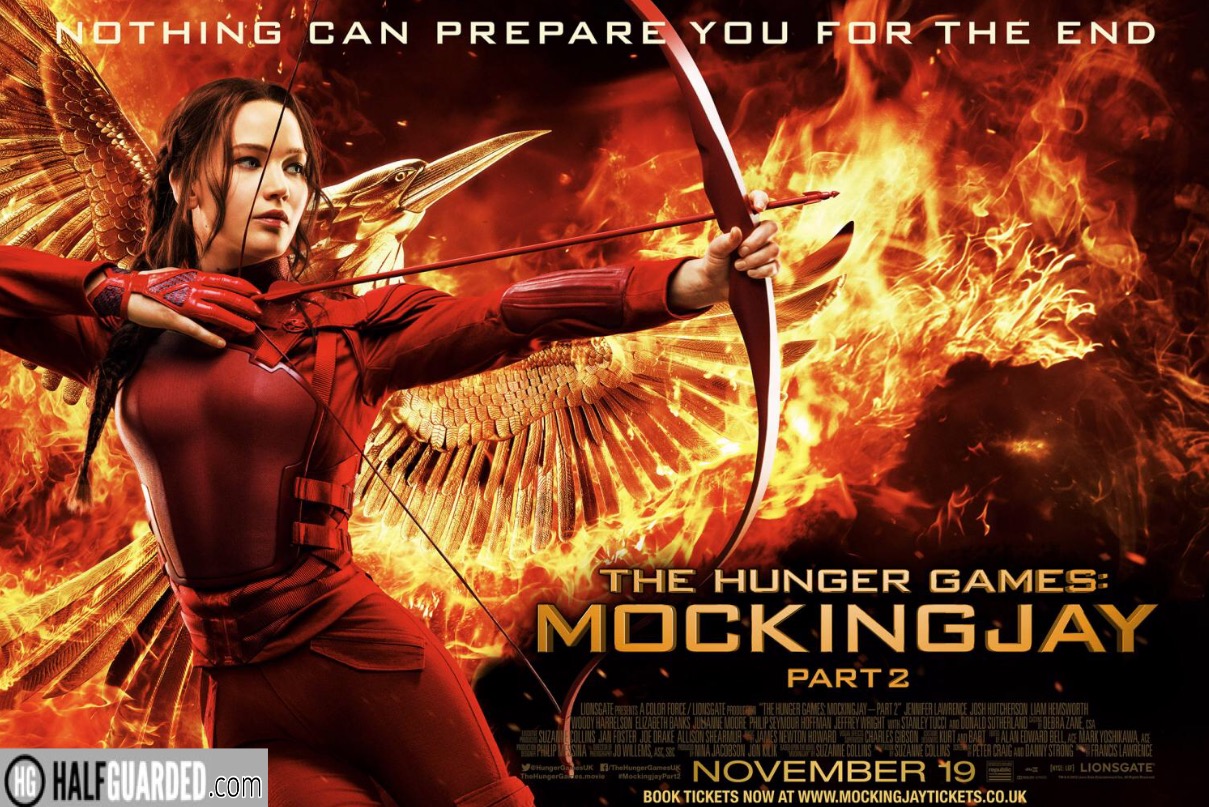

By the time the environs of Cartersville, Ga., are transformed into District 12 (which shouldn’t be hard, since it’s already a community heavily stratified along racial lines overseen by a plutocratic elite and filled to the brim with economically-challenged youths living in the fog of substance abuse and industrial decline), The Hunger Games series will be incredibly outdated. Unless the suits in Hollywood can convince Suzanne Collins to fork over the rights to her franchise for a series of spin-offs and prequels, the recently released Mockingjay Part 2 will be the last major Hunger Games media to come down the pipes for the foreseeable future. And unfortunately, it’s a rather droll note for the series to go out on.

I wasn’t a big fan of the first three films, and I never read any of the books. I’m not the first person in the history of the Internet to drudge up its similarities to the cult Japanese classic Battle Royale, nor am I the first to note how that 2000 film executed The Hunger Games motif so much better. That said, there is so much that movie got right that the Katniss saga never did; as a political metaphor, a character-driven drama and straight-up action-adventure, Battle Royale simply outclasses The Hunger Games in every way.

Despite its highfalutin attacks on corporate culture and reality television, The Hunger Games has never really aspired to be more than just another trashy, dystopian young adult juggernaut. Sure, it’s a bit more nuanced than something like Divergent, but it nonetheless follows the same frustratingly familiar formula: teens live in a stifling utopian/negative utopian society, where the ruling class makes all their decisions for them, but what do you know, there is ONE kid among the masses who has the inherent awesomeness to stand up and turn the tides against those oh-so oppressive adults. Forget the Orwellian overtones, pretty much all of these franchises are nothing more than extreme metaphors for how much teenagers hate their parents for not letting them stay out past midnight on a weekday.

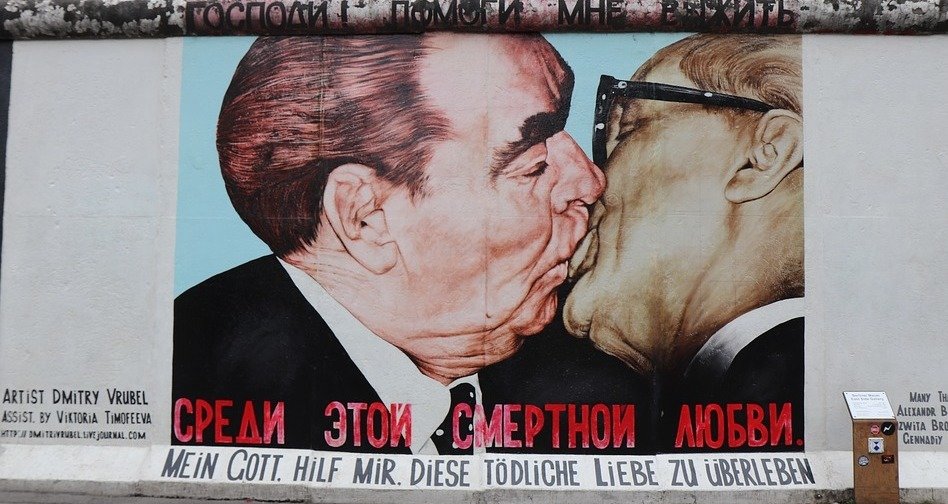

What makes Mockingjay Part Two most interesting, however, is its weirdly out-of-place allusions to the Iraq War. Whereas the first two movies were certainly more rooted in the fantasical (while the first Mockingjay was a strange, cynical attack on propaganda that also seemed to celebrate guerilla violence), the concluding Hunger Games romp feels more like Zero Dark Thirty or The Hurt Locker than Twilight. As a ragtag gang of commando warriors (including Katniss, her dual love interests and a bunch of “documentary” filmmakers) slowly snake their way towards the haunt of franchise villain President Snow, they encounter a series of death traps in the urban ruins, which include pop-up machine gun turrets and collapsing walkways. It’s not too hard to see the parallels between their dangerous trek and the lethal journeys oh-so-many troops in Tikrit experienced as they navigated their way through the I.E.D.-strewn warzones. The absolute kicker is when the resistance is nearly done in by Snow’s ultimate death trap … a barrage of bubbling oil. Jeez, talk about allegorical subtlety!

There is quite a bit of intrigue involving the ulterior motives of the resistance leader (played by Julianne Moore), but even after the oppressive regime falls – and Donald Southerland’s nefarious leader is reduced to stumbling about in a heavily guarded greenhouse, just like Saddam Hussein post-capture – it’s pretty easy to see the big “twist” ending coming. The action sequences are also paint-by-numbers, including a subterranean throwback to Aliens that’s more of cheap imitation than a loving homage.

Perhaps the biggest flaw with this last Hunger Games hurrah is Jennifer Lawrence’s half-hearted performance. It is apparent that she has grown bored playing the franchise’s heroine, and when it comes time for her to display her acting chops, she painfully phones it in. While the series as a whole has been praised for featuring a strong-willed, female protagonist, Katniss really isn’t coming off as Samus Aran in this one; I counted up no less than three sequences in which she was hospital-bound, including an opening scene in which she’s recovering from nearly being choked to death by her brainwashed boyfriend. Nor does she seem that concerned by the morality of her actions anymore; she has no qualms incinerating some of her fellow freedom fighters with explosive-tip arrows a’la Rambo, and she acts astonishingly unemotional after her compatriots fire bomb an entire encmapment of orphans. And not to give away the ending, but the series’ big finale paints Katniss in a regressive supporting role that most certainly does not fit the conteporary independent woman archetype. So much for all that “girl power” hullaballo, I suppose.

After all of the death and destruction leading up to the franchise’s big finish, I was a bit perplexed by its ending. Despite its anti-authoritarian overtones, the finale skirts the old “new boss, same as the old boss” routine and allows Katniss to ride off into the sunset, the cost of her newfound bucolic exisence just a good million or so corpses. I’m not quite sure what the central message there is supposed to be … or more troubling, if the producers of the film even intended for there to be some kind of “greater moral” to the preceding carnage at all.

As a pseudo-sociopolitical work, I struggle to interpret a singular “message” behind The Hunger Games films. As apparent by the on-the-nose Iraq invasion allusions, the films do seem to capitalize on the target audiences’ awareness of the world around them, but as expected, everything is reduced to stark blacks and whites, with a sense of morality that’s hardly consistent. Perhaps the films are nothing more than a parallel for today’s teens’ inability to grasp the adult world, of having responsibilities and interpreting large scale global problems and the like. But after repeated viewings, and especially after screening this latest flick, it seems The Hunger Games mythos is little more than pandering to high schoolers’ desire for in-group approval and their loathing of helicopter parents controlling every aspect of their lives. It’s a celebration of the most childish version of “freedom” imaginable – a world where youth have the independence to do whatever they wish, but someone is still there to bail them out before they have to incur the dire consequences of their own actions.

Mockingjay Part 2 fails to wrap up the franchise in a satisfying, or even categorically consistent, package. It’s a CGI-laden bore with uninteresting characters, faux emotions and a LOT of inconsequential deaths. While some of the hammy acting – particularly, Southerland’s literal foaming at the mouth performance – is enjoyable, the overall atmosphere of the flick is suprisingly lethargic. Like a bunch of coddled teens emerging from the coccoon of suburban adolesence, the light at the end of this tunnel is a drab, grey facsimile of the adult world, where apathy reigns supreme.

As childhood ends, so does The Hunger Games saga: not with a bang, but with the woeful realization that yes, this is all there is to the world around us. In that, The Hunger Games seems to hint upon a scourge that Gen Y fears even more than the icy touch of Death itself; the inevitability … and abject terror … of growing up.

Comments 1