Odds are, if you are reading this, you’re not 100 years old. That means you have no grasp of what the United States was actually like in 1915. All you have, ultimately, are a bunch of old relics to more or less guess what constituted reality at that point in time; archaic newspaper clippings and faded photographs and of course, the pioneering early cinema works.

1915 was a long, long time ago. More than likely, you’re not able to successfully identify who was President of the United States back then, or for that matter, just how many states were included in the Union. Without a Wikiepedia shortcut, you probably won’t be able to name any key books published that year, or any revolutionary inventions patented, either.

One of the few transcendent texts from that year, however, is a film that — to this day — evokes great emotion and debate about the visual medium.

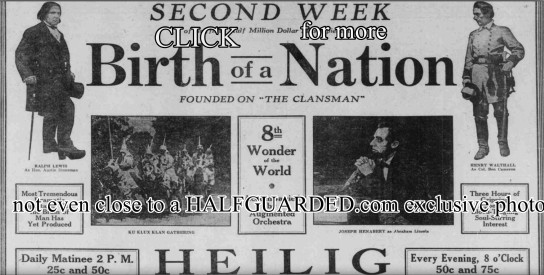

Without question, D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation is the most controversial film ever made. As soon as the film was released, the NAACP staged protests. In some cities, it provoked rioting. As recently as the 1990s, court challenges have been filed to bar the film from public screenings.

It puts film scholars, and in many ways, U.S. historians in general, in a perpetual bind. As arguably the first true “event” picture — providing a technical showcase for what would soon became an inescapable aspect of American culture — its long-term social impact is undeniable.

Equally undeniable, however, is its blatantly racist content. The term “undertone” here is unnecessary, as the unrepentant bigotry of The Birth of a Nation is visible to anyone with a half-functional set of peepers.

Before we even get into the depiction of blacks in the film, the mere fact that all of the actors portraying African-Americans in the movie were Caucasian thespians in charcoal-hued make-up is probably enough to get most of the contemporary population irked. By the time a white actor in blackface proceeds to chase a white woman off a mountain (a scene which heavily implies an attempted rape) — and ESPECIALLY by the time a gaggle of freed slaves shuck and jive inside the South Carolina State House like David Duke-penned doodles — pretty much everybody alive who isn’t a regular contributor to the Stormfront forums will likely be in a state of infuriated disbelief.

Then, there’s the film’s grand finale, with a zombie-like horde of wild-eyed black men encircling a house filled with helpless women and children. Just before the rape-and-murder-hungry ex-slaves move in for the kill, a cavalry stampedes across the hinterlands for a last second rescue attempt — and by the way, that cavalry just so happens to consist entirely of members of the Ku Klux Klan. Adding to its already notorious reputation, the popularity of the movie is also credited with resurrecting the universally-despised hate group in real-life — shortly after The Birth of a Nation was released, KKK membership soared coast-to-coast.

Despite the controversy, the film was a bona-fide smash hit. In fact, it was probably the first true Hollywood blockbuster, marking the first time a movie became a part of everyday American discourse. It’s import reached all the way to the Oval Office: so impressed by the work, Woodrow Wilson held screenings of the film at the White House.

Technologically, The Birth of a Nation was a cinematic breakthrough. Up to that point, not only had most films had a running time of a few minutes, the idea of movies having actual narratives was still something of a novel concept. Exceeding three hours long, the film was among the first to feature extensive outdoor sets, nighttime sequences and sweeping camerawork. To ignore the technical importance of The Birth of a Nation would be like teaching a psychoanalysis class without once mentioning Sigmund Freud.

Many film scholars STILL consider The Birth of a Nation to be the greatest movie ever made about the Civil War. Eschewing the sappy romanticism of Gone with the Wind, the film depicted the fall of the Southern aristocracy in a much bleaker light, complete with battlefield scenes that, to this day, remain cinematic marvels. Its depiction of Reconstruction — the regrettable caricatures of African-Americans aside — is also much more realistic and disheartening than anything viewers saw in the Scarlett O’Hara saga.

Which brings us to a truly unanswerable question: is it possible to extrapolate the technical and cultural significance of The Birth of a Nation from its abhorrent portrayal of black people, and celebrate its social and technological importance independently of its racism?

I’m not even going to pretend that I know the “correct” answer here, of if a “correct” answer even exists. Technically, one could argue that the film itself isn’t technically racist, as it’s nothing more than a film adaptation of a pre-existing racist work — a pro-segregation potboiler called “The Clansman,” penned by notorious North Carolina legislator and obvious white supremacist Thomas Dixon, Jr. Believe it or not, Dixon actually directed an unofficial sequel to “The Birth of a Nation” a year later, an eerily prescient film about America going to war with evil Germans. Alas, that flick — titled The Fall of a Nation, naturally — appears to have been forever lost to the ravages of time.

Interestingly enough, D.W. Griffith himself never really considered The Birth of a Nation to be racist and spent the rest of his career trying to make amends for it. A year later, he released Intolerance, an even more epic motion picture sprawling across centuries, with the central message that bigotry ain’t cool. He addressed the immorality of racism even more directly with his 1919 film Broken Blossoms, which was about a kindly Asian immigrant who sought to save a young woman from her abusive father — a message that’s just a tad muddied considering the amount of “yellowface” going on in the picture, but still. Ultimately, Griffith came to support the censorship of his own magnum opus, telling Variety that the times had changed since the film’s initial release and it probably shouldn’t be shown “as-is” anymore.

Alas, should we toss away a remarkable piece of both U.S. culture and history simply because it presents an unflattering look at the way we once were as a collective peoples?

As offensive as it may be, The Birth of a Nation is nonetheless a socially significant work; it’s the cornerstone of the American motion picture, and if absolutely nothing else, a rather condemnatory time capsule of just how prejudicial society as a whole was a century ago. The film embodies that old maxim “those who forget the past are doomed to repeat it” to an almost comical degree — purging it from the social consciousness is to deny our own transgressions, to pretend that our historical wrongdoings never occurred.

Yes, The Birth of a Nation is ugly and unsettling and embarrassing and infuriating, but its content reveals an ineffaceable truth about the American condition. To obliterate it out of mere convenience means lauding ignorance over acceptance, to forget the vileness it represented ever took place. Forgetting The Birth of a Nation means forgetting the suffering and cruelty of our own ancestors, and the historical antecedents that frame our national narrative on racism to this very day. Forgetting The Birth of a Nation, simply put, means not only denying our past, but embracing our unwillingness to confront the brutal truths of yore.

“Great,” one must remember, does not necessarily mean “good,” or “worthy” or even “moral.” It simply means that something is monumental, of supreme importance for one reason or another.

Considering what The Birth of a Nation says about our shared history as Americans, I’d feel comfortable labeling it as a “great” work of art. As deplorable as its message may be, it’s no doubt a significant commentary on where we have been as a country, and without acknowledging that, there’s no way we can even attempt to make sense of our contemporary situations.

One hundred years down the road, the movie remains a landmark, not only for the cinematic form, but as a visual documentation of the nation’s legacy of racial wrongdoings. Destroying it would mean not the destruction of its racist leanings, but counterproductively, the elimination of among the best evidence we have against America’s long track record of injustice and intolerance.

As much as we may want to, we cannot simply erase The Birth of a Nation from our collective memory. Forgetting the real-world ugliness the film represented then, after all, would be just as unconscionable as praising the movie’s indubitably ill-intentioned message today.